By Anna Ludmilla Strømbæk Henriksen and Jacob Malte Scheye Schytte

The coronavirus pandemic is the global challenge of our time. In the last year, the virus has spread to almost all the countries of the world. In the wake of this, we have faced a period of resurgence of borders. This could eventually lead to a new multi-layered global border regime in which the state wants to protect itself, in this case, from a virus that is increasingly portrayed as an alien intruder. This “closing” system has been embraced by both authoritarian states and liberal democracies throughout the Member States of the European Union. Are borders resurgent in a post-Covid-19 world? What consequences will this have for the free movement?

International challenges and borders as a resource of power

There is a wide variety of both internal and external factors, which are affecting the European Union’s function and legitimacy. One example is Brexit, but also the increasing number of right-wing populist parties, which are receiving more and more consensus throughout the European countries. Moreover, these parties are putting at risk Eu’s fundamental rights, like human rights. These are all symptoms of a challenged Union, where citizens are feeling threatened on their national identity by internationalism and cosmopolitan ideas.

There have been multiple efforts from the side of the Eu to deal with all of these challenges of globalization, including climate change and cyber attacks. However, must most of them have come up short and also the Eu has made several mistakes. Among them, for example, the decision to make a common currency within the Union without creating a common fiscal policy or banking union, or the decision to permit almost unlimited immigration to Germany. This decision has made a “powerful backlash against existing governments, open borders and the EU itself” . All of this has resulted in a wave of anger against global markets, international regulations, representative democracies, and open borders.

Covid-19 has put even more momentum into this process according to which closed borders within Europe are seen as an example of how countries can use them as a tool to protect themselves and their sovereignty against intruders. Therefore, borders can be used as a resource of power to ensure stability within the country and safeguard its identity. As Enemark says in his 2009’s article about pandemics as a security threat: “border protection is emblematic of a narrow, national security mindset being applied to a microbial threat that is inherently transnational in scope”. The use of borders as a power resource is, therefore, more symbolic than anything else.

Debordering and rebordering: the history of borders from feudal governments to territorial states

The understanding of borders goes back to the French Revolution, where the idea of nationalism arose. It generated loyalty, and thus, there was a construction of the state with absolute domination of the government and sharp external borders.

Since the king could not dominate all of the territories, he delegated the power to a vassal to control the areas in his name: this was the so-called feudal government. The territorial state starts to become crucial when the nobles begin to lose their power. Simultaneously, the king became able to control more and more areas through technology. The more territory a king could dominate, the more money and resources come with it. The shift from the territorial system to the national one changes the political legitimacy and the state’s generation of resources. For instance, citizens begin to pay money to the country and not to the king. Borders have been crucial in the creation of the territorial state.

European cooperation was founded in the wake of World War II and was intended to prevent a new war between European countries. The original idea was that by increasing trade between the countries, the war would in practice be impossible. Regarding this, the free movement and residence of persons within the EU was introduced in the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 and is one of Union citizenship’s cornerstones. A so-called debordering of the borders was established through the outbreak of nationalism.

Covid-19 has resulted, as stated, in a rebordering where the old borders again are finding their ways into politics as a tool of power and stability.

Covid-19 and borders

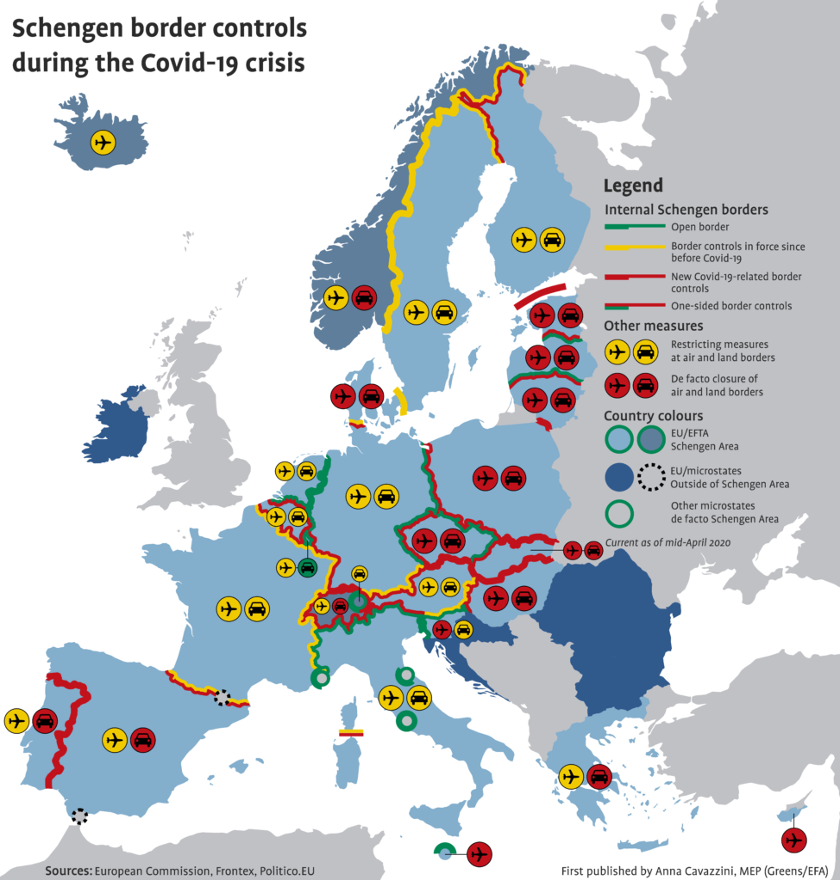

With the coronavirus pandemic, the EU reintroduced enforced borders across the Union to contain the virus outbreaks. This tactic could lead to a possible revival of the old frontiers or the creation of new ones. It not only happened between the Member States but also within the nations. The enforcement of borders has appeared across nearly every European country and with the use of security and military forces. These have been the measures applied to regulate the free movement of people to contain the virus.

The measures applied by governments in the EU were different. However, everywhere there was the same objective to limit the spread of the virus. The efficiency of national health systems relies heavily on the governmental countermeasures that each state adopts. As seen with some Member States (Eg. Sweden and Italy), there are substantial differences across the approaches. However, one can argue that tightening border control to battle a pandemic is more of a symbolic act rather than a substantial countermeasure. The word “pandemic” suggests a trans-national crisis, and it is just what we have experienced during the past months. Indeed, variants like the Brasilian and South African ones spread rapidly within the EU despite strict internal and external border patrol measures. Tightening border control to fight diseases has historically been a common countermeasure. However, since it often had a limited effect, one might wonder why most national governments so firmly grabbed for this countermeasure.

Will free movement be under threat in the future?

There are relevant differences between the contexts of previous virus outbreaks and Covid-19. As earlier stated, the coronavirus arrived at an already difficult time for Brussels. Indeed, Brexit, the growing resistance towards migration flows, and even bigger geopolitical tensions are already challenging the EU legitimacy. All of these elements might have a direct causal impact on the political will to reinforce borders on immediate virus-containing concerns. Only future studies will be able to tell ff the currently closed frontiers are effectively limiting the spread of the virus or not. However, the real question is when will it be safe to remove them again.

It may be that in the coming years, free movement of people might not be a right on which we can easily rely. For what concerns migration flows, the common belief is that Brussels has failed to solve the crisis. Especially in the Southern and Eastern European countries where, due to their geopolitical location, the feeling of having been left alone by Brussels is present. It is a harsh truth, but here the pandemic could come in handy to legitimize border enforcement. If considered as effective, affected countries could use it as an instrument of taking back territorial control from the EU.

The virus has so far not shut down Schengen. However, it has activated paragraphs in the legal texts that allow for extraordinary and unprecedented measures. All of them aim to reduce the free movement within the area. The work of getting the Member States to return to the “normal situation” without border controls may turn out to take longer than the work of breaking the proliferation curve. Will EU citizenship and the right to free movement continue to have added value, and how will it affect an already declining belief in a cosmopolitan EU?