By Michele Debernardi and Federica Massafra

Amid suspicion on COVID-19 vaccines spreading faster than the very virus, alarming side effects, and missing doses, the goal of reaching herd immunity seems still only a teasing mirage. But has there been sufficient institutional transparency to win off even the most radical antivaxxer, or are citizens right to stay clear of too rushed a strategy?

The conclusive remark of most official communications by the EU about the common vaccine strategy reiterates that “no one is safe until everyone is safe”. This serves a few institutional purposes: it invites Europeans to solidarity towards low- and medium-income countries in sharing vaccine supplies; it strengthens the perennial goals of the EU itself, namely fostering integration and the single market; and it serves as a self-explicatory message specifically directed to vaccine sceptics.

This priority is evident in all Commission documentation issued since June 17th 2020, whose focus has indeed been on describing how an authorization process that usually takes up to 10 years was sped up into just a few months. The declared objective consisted in ensuring quality, safety and efficacy of vaccines by securing sufficient supplies for Member States through Advance Purchase Agreements (APAs) with individual pharmaceutical companies. In fact, central procurement reduces transaction costs while increasing the bloc’s leverage in negotiations, so as to obtain economies of scale, scope and speed.

As a matter of fact, regulatory flexibility allowed the Commission to secure a certain quantity of doses at a given price by covering some of the high fixed costs the producers would face using the Emergency Support Instrument (ESI) for financing. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) set up an independent task force (COVID-ETF) to monitor all stages of development, providing constant feedback during the clinical trials so as to have a quicker assessment of the final data (rolling-reviews).

The language requirements of documents, packaging and labelling of doses was thus alleviated. Conversely, the biggest shortcut was that of conditional authorisations, based on non-exhaustive yet positive data in order to move on to the next phase of trials with obligations to compete verifications afterwards – as long as the “benefits of the product outweigh the risks”.

The most substantial body of data thus comes from a comprehensive “pharmacovigilance” system, ensuring that any information collected post-marketing is evaluated as soon as possible and that appropriate responses are taken to safeguard public health. Therefore, prompt communication among countries becomes of paramount importance.

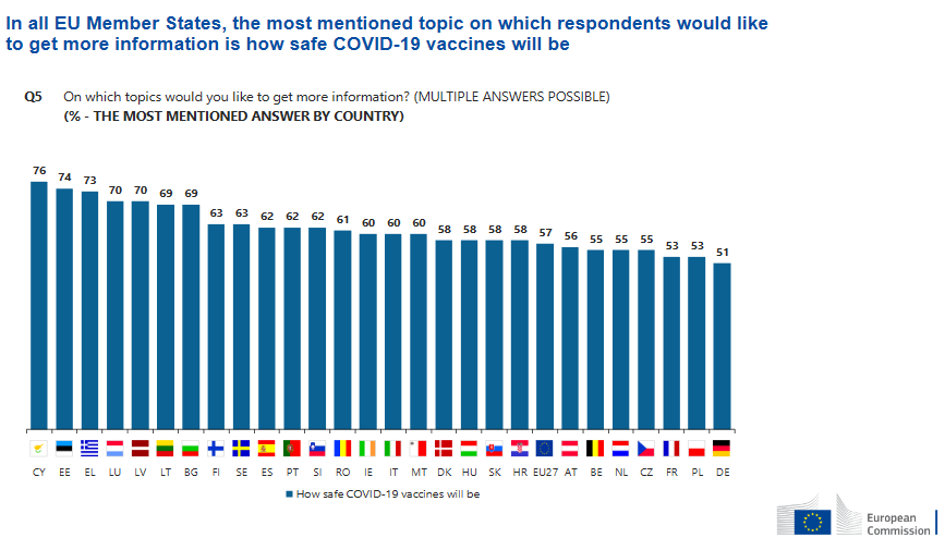

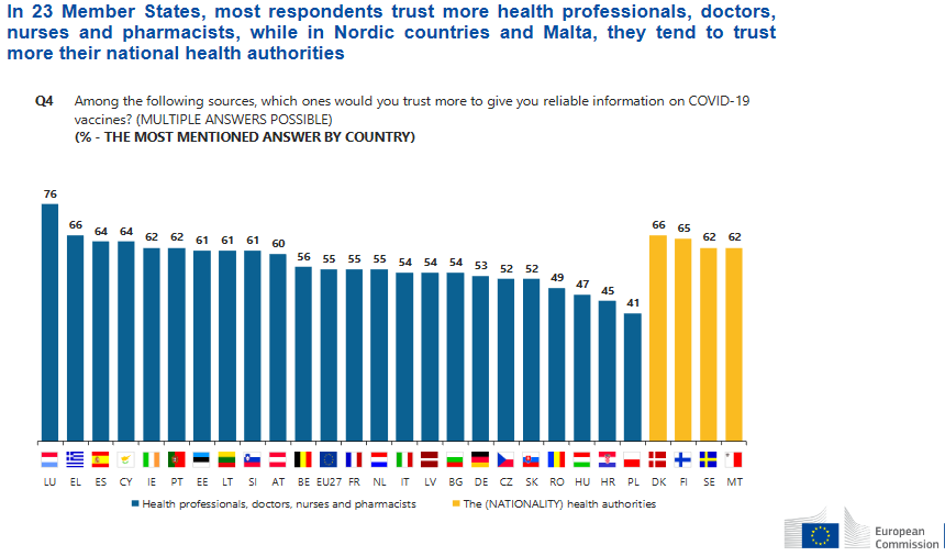

States knew they would have to be prepared on the lack of confidence in vaccines, especially considering the crunched timespan for the covid emergency. But if negotiation has been an EU-level effort, then perhaps national sensationalist media were not the best vehicle to deliver data to the general public.

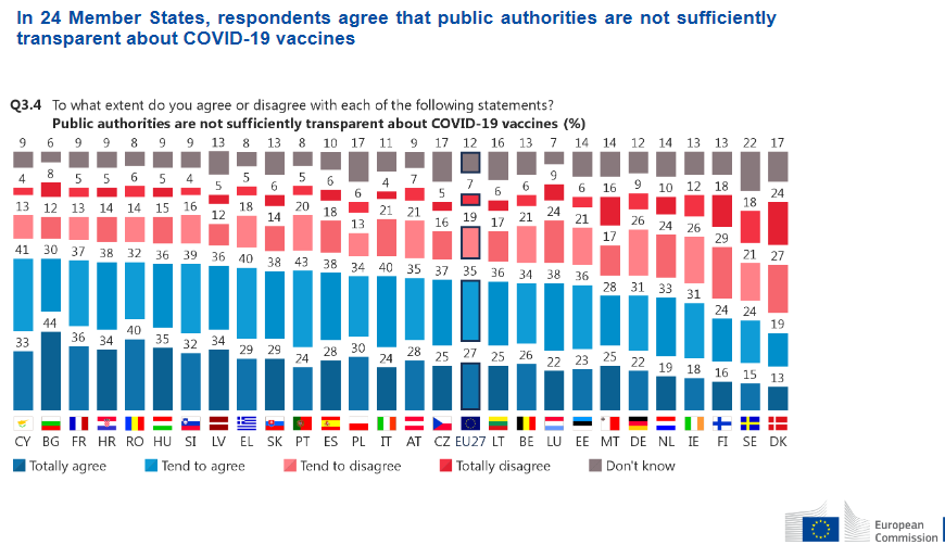

All this doesn’t concretely help with scepticisms and, most importantly, not much is revealed concerning the negotiating process. APAs contain liability arrangements that allegedly do not alter the burden of proof (borne by manufacturers) to satisfy safety requirements. APAs are confidential, as openly admitted by the Commission, due to competitive tendering processes.

But without absolute transparency, the result is distrust. Ursula Von der Leyen acknowledged she had a too optimistic attitude in APAs concerning sustained production and delivery, yet insisted that no corners were cut in terms of safety. This actually suggests that the above can be understood as one of the reasons why the EU is lagging behind other countries in administrations.

However, AstraZeneca represents the most salient case both in terms of supply shortages and suspected safety issues. After the official publication of a redacted version of the AstraZeneca APA, the leaked full document revealed the impossibility for the EU to sue the company in case of belated delivery or safety issues. This clearly sparked further uncertainty and even paranoia.

Inadequate transparency proves particularly frustrating, even counterproductive when the undisclosed information would serve only as additional evidence in support to the cause, or might convince a few more naysayers to get vaccinated.

The Commission has worked intensely to build a diversified portfolio of vaccines against COVID-19. It concluded contracts with Johnson and Johnson, AstraZeneca, Sanofi-GSK, Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, BioNtech/Pfizer, CureVac, and Moderna. So far, the Commission has secured up to 2.6 billion doses, and has fulfilled its commitment to ensure “equitable and affordable access” to vaccines. This represents an important cost for the EU health system, involving generous public funding.

The above encouraged public opinion to support calls to make vaccines a global public good. Trials to evaluate vaccine safety are also performing under an unprecedented level of public scrutiny, far beyond the usual public interest for drug development. Therefore, transparency of negotiation has become a central issue.

In a statement to the European Parliament on transparency of the purchase and access to COVID-19 vaccinations, Commissioner for health and food safety Stella Kyriakides recognised that, “due to the highly competitive nature of this global market, the Commission is legally not able to disclose the information contained in the contracts” unilaterally and without the consent of the parties involved. In fact, the companies require that sensitive business information remain confidential. “There are also rules”, Kyriakides adds, “that protect the tendering process”.

A common document, published in January, has the major pharmaceutical companies recognising the importance “to preserve, build and sustain public confidence in COVID-19 vaccination by continuing to make and communicate policy decisions based on robust scientific evidence”. They also highlighted the emergence of “discussions regarding dosing strategies that may not be supported by the authorized labelling or published clinical data”, wishing for the “transparent deliberation of the available data”.

The measures to do so include speeding up publication of documents, in particular the management plan and the clinical trial data, while also protecting privacy rights. Data sharing could also enhance global collaboration and improve control of future outbreaks like COVID-19.

However, the pharmaceutical companies still protect information such as development and production plans, and transparency on negotiation is now advocated by many. Some importantcivil society organisations – including the European Public Health Alliance and the Corporate Europe Observatory – posed request, asking for the establishment of a reading room by the Commission, the access to concluded deals by national parliaments and the public, and the disclosure of non-commercial aspects of these contract.

Some members of the European Parliament called for more clarity on vaccine contracts, which is the best way, they say, to deal with uncertainty and disinformation. Such requests, we think, are crucial. Public confidence in vaccines remains fragile, and high levels of transparency in negotiation of contracts can help – as Ursula von del Leyen put it – to combat “the myths, misconceptions and scepticism that surround the issue”.