by Pietro Maccabelli

Since the end of World War Two, Europe has been one of the major destinations for migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. Particularly from the 1980s onwards, this growing migratory pressure progressively turned into a popular feeling of racial rejection that strongly influenced the following migratory policies of the EU. These policies were – and still largely are today – rooted on the endeavour to significantly reduce the incoming of migrants through the externalisation and securitization of European borders.

This has been an overall linear approach during the last decades with only a few exceptions. Nevertheless, the influx of migrants from Ukraine to the EU, triggered by the Russian invasion of the country, has generated a completely different response on behalf of the European countries and the EU as a whole.

Should we talk about a longstanding Union policy change or just of an isolated case in its general migratory and asylum policies?

The restrictive asylum policies of the EU over time

In the last decades, the European Union approach to migration has been deemed quite controversial. While claiming to be the global leader in human rights diffusion and protection, the European management of the migration flux, based on pragmatic and realist considerations, has made clear that there is a discrepancy between how the EU depicts itself to the world and how it acts.

Worldwide, the EU remains one of the most active political entities to guarantee high humanitarian standards within its borders. Nevertheless, when it comes to migrant management – especially if from the African continent or the Middle East -, the Union approach differs considerably.

Even though European institutions are not directly responsible for the violation of the refugees rights, externalising and trying to secure the EU borders they do that indirectly. In fact, they subsidise and delegate the management of those migrants to non-European countries that are notoriously (in)famous for their human rights violations.

This process of externalisation and securitization of the EU borders is clearly visible with reference to both the African and Middle Eastern migration flows.

The African case

With respect to Africa, the EU has repeatedly embarked on endeavours to pressure African states to cooperate on the management of migration. EU institutions have tried to do that using the main means at their disposal, that is, the EU’s financial resources.

The main initiative in this respect is the EU emergency trust fund for Africa. As stated by the European commission, this 1.8 billion euro fund is aimed at “granting stability and addressing root causes of irregular migration and displaced persons in Africa.” The funds are geographically focused in the Sahel region, the Horn of Africa, and North Africa. Its main goals are providing economic programmes aimed at boosting the employment level in African countries, increasing food security, fostering migration management where the migration routes transit, and strengthening the rule of law, border management, and conflict prevention in those states.

Of similar orientation is also the more recent Commission’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum, launched on September 2020, which added to the aforementioned goals of the EU emergency trust fund the urgency to sign returns agreements with third countries and the necessity of a less unbalanced distribution of responsibilities between member states as far as migration is concerned.

One may argue that these initiatives have the potential to ameliorate the situation in the countries of transit and departure of migratory flows, but it is more realistic to acknowledge them as policies aimed at externalising the responsibility for migrants management. These responsibilities are given to deeply unstable countries whose human right protection is more than questionable.

These actions have also caused great suffering, as it is clear in the Libyan case, where the EU has trained and financed the coast guard of the country and subsidise the construction of refugee detention centres, indirectly contributing to creating a humanitarian disaster.

The controversial relationship with Turkey

In 2015 the Syrian migration crisis generated around 1.3 million asylum applications to the European Union, and made clear to European states that they needed a way to control the Middle Eastern migration routes.

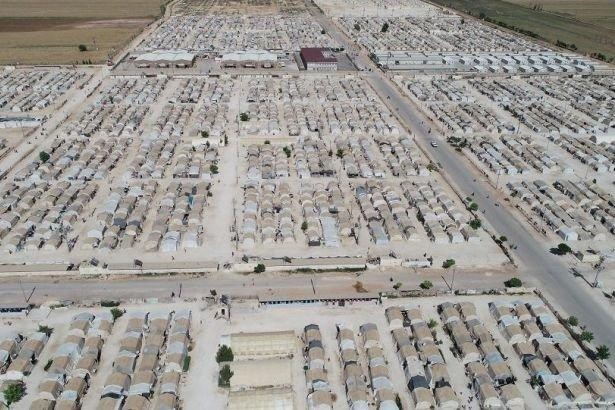

To ensure the externalisation and securitization of the European borders in this geographical context, the EU has exploited the potential of Turkey as the perfect gate-keeper for the influx of migrants coming from the Middle East. An agreement between Brussels and Ankara was struck in 2016 providing the Turkish government with approximately 3.2 billion euro yearly for the construction of migrant facilities aimed at retaining them outside Europe.

The European council representatives referred, in the press release following the deal, that “all new irregular migrants crossing from Turkey into Greek islands as from 20 March 2016 will be now returned to Turkey”. Moreover, Ankara stated that “Turkey will take any necessary measures to prevent new sea or land routes for illegal migration”.

The agreement generated the expected outcome, with the number of arrivals presenting a 9 fold decrease – from more than 800.000 in 2015 to approximately 36.300 the next year -, so the deal was recently renewed in March 2021.

It is nevertheless important to stress that, even though the number of refugees reaching Europe from the Middle East has significantly dropped, the EU-Turkey deal has resulted in great human suffering and human right violations. Turkey is by now, with roughly 3.7 million refugees, the first refugee-hosting country in the world, but it lacks the appropriate facilities and the administrative capacity to manage all these people. As a consequence, the refugee camps are overpopulated and are in very poor healthcare conditions. Moreover, in violation of the non-refoulement principle stated in the UDHR, unlawfully forced returns to the northern part of Syria have been documented by several NGOs and Human rights watch agencies.

Overall, even in this case the EU refrained from addressing the problem at its roots by simply delegating the burdens of managing migration flows to a state with less scruples about human rights violations.

The Ukrainian exception to the rule

Immediately after the outburst of the Russian-Ukrainian “de facto war” (at the time of writing there have been no formal declaration of war), even the more anti-migration European countries made it clear their willingness to welcome the war refugees from Ukraine. Even European nationalist politicians that over time have largely built their political consensus on anti-migration arguments, have rediscovered themselves as strongly committed to welcoming Ukrainians fleeing from the war.

Also at the EU level, great changes have been witnessed. Indeed, for the first time in the Union history the Temporary protection Directive was activated. Since the 4th of March, it has become applicable and has given protection and official legal status to all the people escaping from Ukraine.

Without belittling the importance of these actions, it is clear that they represent an exception rather than a longstanding change of policy approach towards the issue of migration. This exception was made possible by the European perceptions of Ukrainians as closer to the Europeans not only in geographical terms, but also on a cultural, religious, and economic level.

Moreover, the extensive media coverage that the Ukrainian crisis has received since the beginning of the war has created an incredible sense of urgency and solidarity. This conflict has therefore entered the European political and public debate in a way that other Middle Eastern or African wars have not even come close to in the past.

For these reasons, it remains quite unrealistic to think that the unfolding of these recent events will bring the Union to a structural rethinking of its Asylum policies.

Future perspectives for European migration policies

The contradictions between the European Union rhetoric and its practices is evident when looking at the Ukrainian crisis. The option of a shift in the Union’s overall migration policies after the Ukraine refugees crisis is quite remote. Indeed, it is likely that in the near future the Union will continue in its endeavours to externalise and secure its borders. The reasons for this approach are easily understandable and rooted in realpolitik considerations.

According to the 2018 standard Eurobarometer, immigration is perceived as the most important concern of European citizens (40%). Since the growing fear of “The other” generally translates into political consensus for far-right populist and euro-sceptical parties, it is of paramount importance to the very existence of the Union to find solutions for the migratory problem.

It is also clear that, to this day, the European Union has not the capabilities to integrate the millions of economic migrants and refugees that try to access the continent. At least, this is not possible without seeing the European cultural cohesiveness and the welfare systems of its member states collapsing.

The best viable way to tackle the migratory issue is therefore trying to improve the living conditions in the countries of departure and transit, in order to decrease the number of people hanging towards the Union’s borders. The question of whether the right way to do that is through the provision of economic support for the autocratic regimes governing those countries, however, remains a strongly contested one.