By Gaia Bernardini and Onur Koroglu

By Gaia Bernardini and Onur Koroglu

If the famous Italian journalist Beppe Severgini’s assessment on the United States was made about the European Union, an important step will be taken towards the purpose of this article: “If I were European, I would write a short letter to the Commission and say that ‘Hey guys! How can be possible that after survived all these wars, fought against dictators, gave to the world a lot of ideas, inventions, and also Napoleon, but still not get together? I want to talk to the Planning Department!”

As it was for the 2008 war in Georgia, can we say that, after the 2014 Ukraine crisis, the EU resume very quickly “good relations” with Russia? Why?

When the crisis broke out in 2014, the EU Member States held a heavy cohesive position towards Russia. In the Summer of the same year, the European Council approved sanctions in finance, military, and dual-use goods fields. In June 2020, the Council decided to renew them until 31 January 2021.

This time the idea was that finally, the EU was able to behave differently than in 2008 and could agree on a collective response. The Member States were able to put aside their interests during the discussions within the Council and find the best way to deal with the major crisis that was occurring.

Ukraine crisis was threatening the EU’s fundamental values, the European integration process, and the security of the region. However, Bruxelles was capable, against all previsions, to agree on a common way to act against Russia with the use of sanctions. It was unexpected, mainly because, before the crisis, national interests prevailed over shared views. However, two events changed the behavior of the Member States: the annexation of Crimea and the downing of the MH17 plane. Thus, the Council decided the adoption of sanctions in summer 2014. Despite this mutual decision, relations with Mosca did not change, remaining the same as before. Sanctions’ effects were questionable. Moreover, foreign and security policies remained unchanged. Why was the EU not able to change its perspective towards Russia?

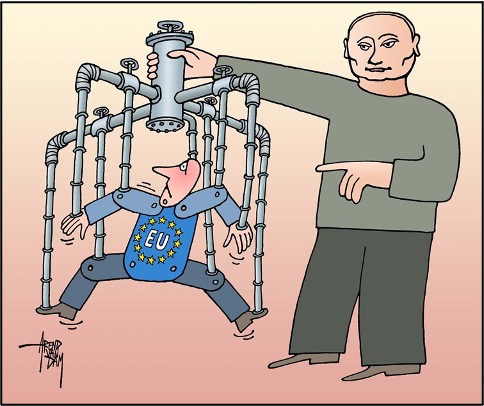

The main reason why the EU was reluctant to change the relations with Russia is the issue of energy security. There is an “energy dependence” relationship between Mosca and Bruxelles because the EU relies on Russia for more than 44% of imported gas, according to Eurostat data of October 2020. This “energy dependence” has increased with the Union’s expansions of 2004 and 2007. The following table illustrates the Union’s dependence on Russian natural gas:

The trade with Russia is one of the broadest and most strategic commercial relationships of the EU. For what concerns Mosca, energy exports to Bruxelles are an essential part of its foreign trade.

For these reasons, energy security was one of the main concerns for policymakers in the EU during the decisions to take sanctions against Russia. Moreover, gas was the most politically sensitive product because half of its imports from Russia passed through Ukraine. The “FEAR” was that the EU energy security could be affected by this political crisis. This problem mainly concerned Eastern states that are more dependent on Russian gas. Therefore the EU-Russia gas trade continued and intensified. It happened especially between 2016 and 2018, according to what was reported by Gazprom Delivery statistics in 2019.

Some Member States, especially the Eastern ones, consider the cooperation between Mosca and Bruxelles in the energy field as a political matter. They fear a strong Russian influence in European affairs and possible heavy pressure. Because the economic dependence of many former Soviet Republics and communist bloc countries on Moscow seriously coincides with the above map of energy dependence. Therefore, these countries “avoid over-angering” their Russian adversaries in any crisis. In this way, they strengthen the position of Moscow at the crisis table, reducing the bargaining share of the EU.

Russia is aware that it has an advantage on energy dependence and does not hesitate to express it openly. It is evident in the statement of Russian President Vladimir Putin regarding the European role in another crisis between Ukraine and Russia in 2009: “(…) Even if the EU repair the pipelines, which natural gas will they fill these pipes?”

This statement explains why the Union mediated efforts to calm the Ukraine-Russia conflict, even when it reflamed in 2014. The lack of energy resources of the European continent has played a big part in the effectiveness of Russia. Thus, the European Union is a natural customer of Russia, where raw resources such as coal, crude oil, and natural gas are abundant. So much so that this trade is vital for the Union. It is imperative to bring energy from the outside for this elderly continent, which has no energy resources but is home to the world’s largest economies. But this unbalanced picture could easily throw the Union into the middle of energy crises, as seen in the 2014 crisis.

Since the 1973 Oil Crisis, the Union has been trying to create many legislations to ensure energy supply security. Especially, since 2006, due to the deepening crises between Russia and Ukraine, the European Union seems to have come a long way in terms of energy security and energy supply. European Commission (2006), Green Paper: A European Strategy for Sustainable, Competitive and Secure Energy, European Commission (2007), An Energy Policy for Europe, European Commission (2008), Second Strategic Energy Review – An EU Energy Security and Solidarity Action Plan are just some of them. In almost all of these legal texts, the central purpose is “ensuring the security of energy supply“. However, it is clear that even if the Union is constantly “repeating” on this issue, it has not been able to carry out an effective policy. So, whose favor is this? Moscow or Brussels?

Despite the initiatives above-mentioned, the energy policy of the EU appears based on documents and reports released as a result of meetings and negotiations. Moreover, projects expected to produce solutions to possible energy crises are still in the “planning stage” or not implemented. Thus, the Union is facing problems in the field of energy that could have irreversible consequences.

However, it seems very difficult for the Member States to abandon oil and gas and turn to renewable energy sources. It appears crystal clear in the “hard exam” the Union gave during the Ukraine Crisis. Thus, another reason for the ineffectiveness against Russia comes to light. In conclusion, even if the rise of Russian gas supplies is not related to politics, it is a signal of the strong dependence of the EU on Mosca. Thus, it gives us the possibility to reflect on why the EU was not effective against Russia after the 2014 crisis because “they needed and they need her”.