By José Roberto Coelho Filho, Marta Pompili and Nejma Rafii Juliette

On March 1st, 2021, the EU-Armenia Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA) between the EU, the European Atomic Energy and the Republic of Armenia fully entered into force. The agreement, whose signature dates back to November 2017, drives the relation between Brussels and Yerevan in areas of mutual cooperation. But is it authentically a step forward?

In the words of HR/VP Josep Borrell, “the entry into force of our Agreement comes at a moment when Armenia faces significant challenges, our Agreement aims to bring positive change to people’s lives, to overcome challenges to Armenia’s reforms agenda”. Nevertheless, beyond formal declarations, many obstacles remain for the deal to become a truly comprehensive engagement. In fact, the 350-page document appears a substantially less ambitious version of the Association Agreement negotiated by Armenian and the EU backin 2013.

But why so? At that time, then Armenian president Serzh Sarkisian unexpectedly scuppered the deal after Russian president Vladimir Putin visited Yerevan. Following that event, Armenia joined the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), led by Russia, in 2015. This was considered a rout for the EU as Armenia preferred to place itself within Moscow’s sphere of influence. By not joining the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA), Yerevan was denied access to Europe’s Single Market. For some, that step could have been the first towards stricter Armenian relations with Brussels, maybe even the opening of a longer-term path towards EU accession.

Thus, while at a first glance CEPA apparently represents an “important milestone”, a clear step forward in the relationship between the EU and Armenia, reality could indeed be more nuanced.

Is Moscow third-wheeling between Brussels and Yerevan?

Armenia is no member of the EU but has been part of the Council of Europe since 1999. Furthermore, the country is a member of the Euronest Parliamentary Assembly and a party to several treaties such as the European Cultural Convention, the European Higher Education area and, most importantly, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

Therefore, signature of the EU-Armenia Partnership Agreement (PA) in 2017 did not come out of the blue. The two parties have maintained close ties since the collapse of the Soviet Union, with the signature of the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) in 1996 which provided a legal framework for bilateral trade relations. Additionally, in 2004 Armenia and other countries of the South Caucasus have entered the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), more specifically the Eastern Partnership.

However, trade was only supposed to be the first step. Indeed, it allowed the EU and Armenia to negotiate the Association Agreement, a more inclusive deal which was set to be signed in 2013. Such agreements are a tool used by the EU in the context of the ENP, aiming at reducing tariff barriers in exchange for political reform, which was not achieved due to Russian pressure on Yerevan. As a matter of fact, Armenia is dependent on Russia for its own security, being a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization, seen as a counterbalance to Azerbaijan’s increased military spending between 2011 and 2013.

Nevertheless, despite Armenia’s strong ties within Moscow, since the signature of CEPA in 2017 EU-Armenia relationships have improved. In April that year, Armenian prime minister Karen Karapetyan said the country wanted to become a bridge between the EU and the EAEU, stressing that the two were not incompatible, and also opening to what has been understood as a more pro-European, and generally pro-Western, attitude.

So, does CEPA really constitute such a bridge?

CEPA: state of the art

Due to Armenia’s membership in the EAEU, CEPA does not include removal of tariff barriers between Yerevan and the EU, nor a Preferential Trade Agreement. Partnership, however, does include political and economic cooperation, as well as promotion of democracy, rule of law and human rights, the EU’s (allegedly) fundamental values. Such values were affirmed and supported precisely at a time in which Armenia suffered an attempted military coup on February 25th.

The socio-political crisis that the country has been through dates back to the 2018 Velvet Revolution, a series of peaceful protests that prevented Serzh Sargsyan from entering his third term as prime minister and resulted in opposition leader Nikol Pashinyan obtaining that position instead.

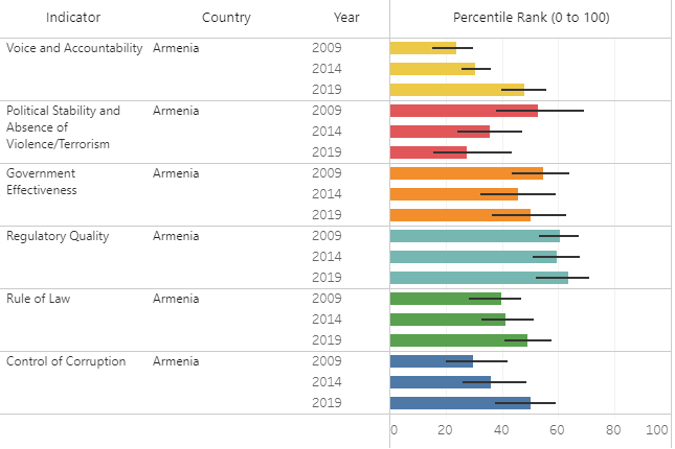

Indeed, the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) in 2019 accounted for the evolution of the Political Stability voice in Armenia (see the figures below). On a scale from 0 to 100, where 100 indicates the highest standard, Armenia was given a score of 27.62 – down from over 35 in 2014.

Against such a background, the agreement aims to promote cooperation in seven key points.

Firstly, considering the business environment, at a moment when the level of unemployment in Armenia is currently 20.21%, the agreement aims to increase employment rates, through the enhancement of regulation and the creation of new jobs. Creation of business opportunities is further encouraged through adherence to international standards and the liberalisation of bilateral trade in many sectors.

Moreover, the elimination of barriers between Armenia and the EU advances towards the reduction of differences regarding regulations, metrology and market surveillance particularly for the Caucasian country. The EU is today the latter’s first trade partner, accounting for about 30% of its exports.

With regard to law, rights and institutions, the goals of CEPA are the defence of fair rules in property rights frameworks and public procurement, improvement of labour standards, improvement of nuclear security, consumer protection, product safety and fight against organised crime.

As for the environment and connectivity, the agreement promotes a cleaner environment through adoption of EU standards. Some initiatives concern European investments in the Armenia-Georgia Energy Exchange, as well as in transport routes in the Sisian-Kajaran Road Project and in the environmental protection of Lake Sevan, pushing Armenia one step further in energetic policies.

Furthermore, the agreement aims to improve the quality of Armenian education thanks to EU training and by promoting lifelong learning as well as upholding the convergence with the EU Agenda for Higher Education Area. Armenian universities were also granted access to joint research programmes under the Horizon 2020 and the EU4Innovation programmes.

In conclusion, reinforcement of democracy and human rights represents a fundamental pillar of the partnership. Particular attention is payed to fair and free elections, freedom of the judiciary and fair trial. A Civil Society Platform has also been established, with the objective of monitoring the implementation of the agreement and providing recommendations.

What’s next?

As discussed, the deal’s inherent limits are mainly due to the extent to which Russia still exerts influence on Yerevan.

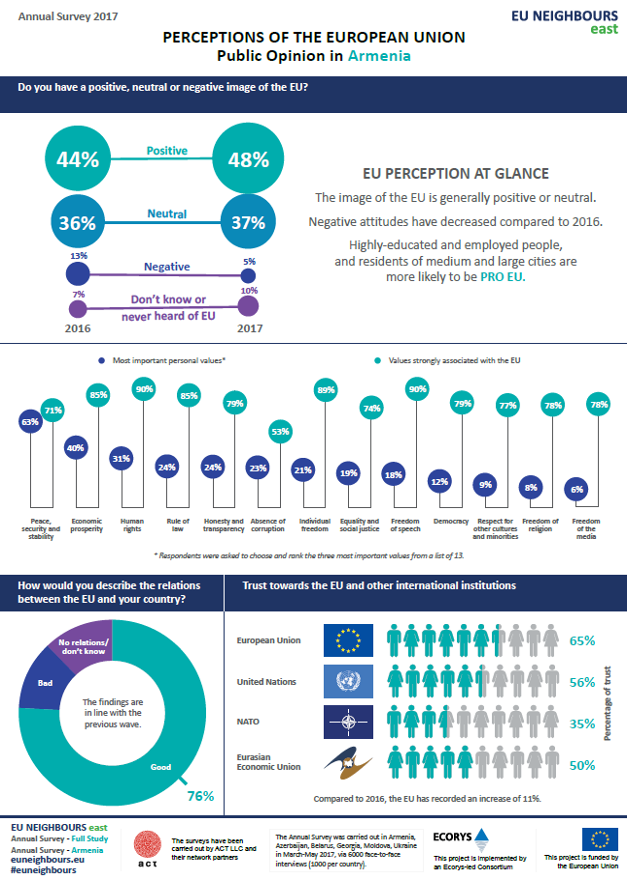

Not surprisingly, political analyst Eric Hacopian contended that ratification of CEPA will not change Armenians’ opinion and concerns regarding the EU (see the graph below). According to him, the latter “lost this country in those 44 days of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh last year” due to its own inaction.

From September to November 2020, in fact, Armenia and Azerbaijan engaged in yet another armed conflict over the highly disputed Nagorno-Karabakh territory. The ensuing ceasefire brokered by Moscow on November 10th (de facto excluding the EU) obliged Armenia to return the Agdam, Kalbajar and Lachin Districts to Azerbaijan, re-igniting political tensions and resulting in the population calling for Pashinyan’s resignation. When CEPA entered into force, Armenia-EU relations had thus reached a low-point in which the Union had failed to establish itself as a pivotal player in the South Caucasus corridor.

As a matter of fact, in the post-Soviet era, while trying to find areas of cooperation with the West (and the EU in particular), Armenia also maintained strong ties with Russia: a bilateral attitude that is still in place today. Interestingly enough, following ratification of CEPA, Russian defence ministry’s Zvezda TV claimed that “Armenia was going to associate itself with the EU”. Moscow immediately received official complaints from Yerevan, after which Zvezda TV apologised to the Armenian ambassador in Russia.

What’s next now? On the one hand, despite wishful thinking arising from the mentioned ratification, Armenia may still reinforce its commitment towards Russia and the EAEU, something that is, after all, arguably coherent with Armenia’s long-standing geopolitical interests. Conversely, Yerevan’s strained relationship with the EU may be limited to areas of more pragmatic cooperation.

On the other side, considering the country’s moderate public opinion and widespread concerns with regards to the EU, the latter should perhaps focus on reaching out to civil society so as to develop more meaningful relations concerning economic and political matters as well as strengthening cooperation through the Eastern Partnership.

In light of the above, Armenia currently seems to be holding its foot in two shoes. Nonetheless, CEPA undoubtedly constitutes a significant step forward in the country’s apparently slow shift towards the West. Even so, if geopolitics does matter, Yerevan might still be too far from Europe both from a geographical and political standpoint.

After all, Russia still plays too central a role for Armenia’s self-sufficiency for the latter to risk alienating the former’s favours. However, if the EU is really to take coherent steps to strengthen cooperation, and to assert its own role as a key actor in the area, we might as well witness a much closer relationship between Yerevan and Brussels – maybe even a “full marriage”.