By Rachele Vedovelli

Climate change, global warming, sustainability, green transition, clean energy – these are only some of the expressions and concepts that have monopolized the public debate in the last few years and occupied international and national political agendas. The scientific community and international organizations such as the UN have been underlining the compelling necessity of reducing our environmental footprint in order to mitigate what it already seems to be an inevitable consequence of our actions. Substantial environmental damage is already under everybody’s eyes, with biodiversity and ecosystems at risk, water and air polluted, and forests destroyed – just to mention some. This XXI-century environmental crisis has become so serious that policies aimed at protecting the environment are being implemented worldwide both to make polluters accountable – for instance, at the EU level the so-called ‘polluter pays principle’is applied, even if it has its shortcomings -, and to make production processes more sustainable – the use of new, energy-saving technology, or the transition to renewable energy both for firms and households are just a few examples. Environment is becoming so important that even national States are starting to consider it a common good to be protected and preserved for future generations. For instance, at the beginning of this year, articles 9 and 41 of the Italian Constitution were modified to become more inclusive in terms of protection of the environment, biodiversity and ecosystems as fundamental elements for human life to protect even to the detriment of private economic initiative. Environmental issues have become pivotal at the European level as well. The European agenda proposed by the new President of the European Commission, Ursula Von Der Leyen (2019-2024), is greener than it ever was: its strong point is the now famous European Green Deal, whose objectives are framed in the ambitious 8th Environment Action Programme.

What is the European Green Deal?

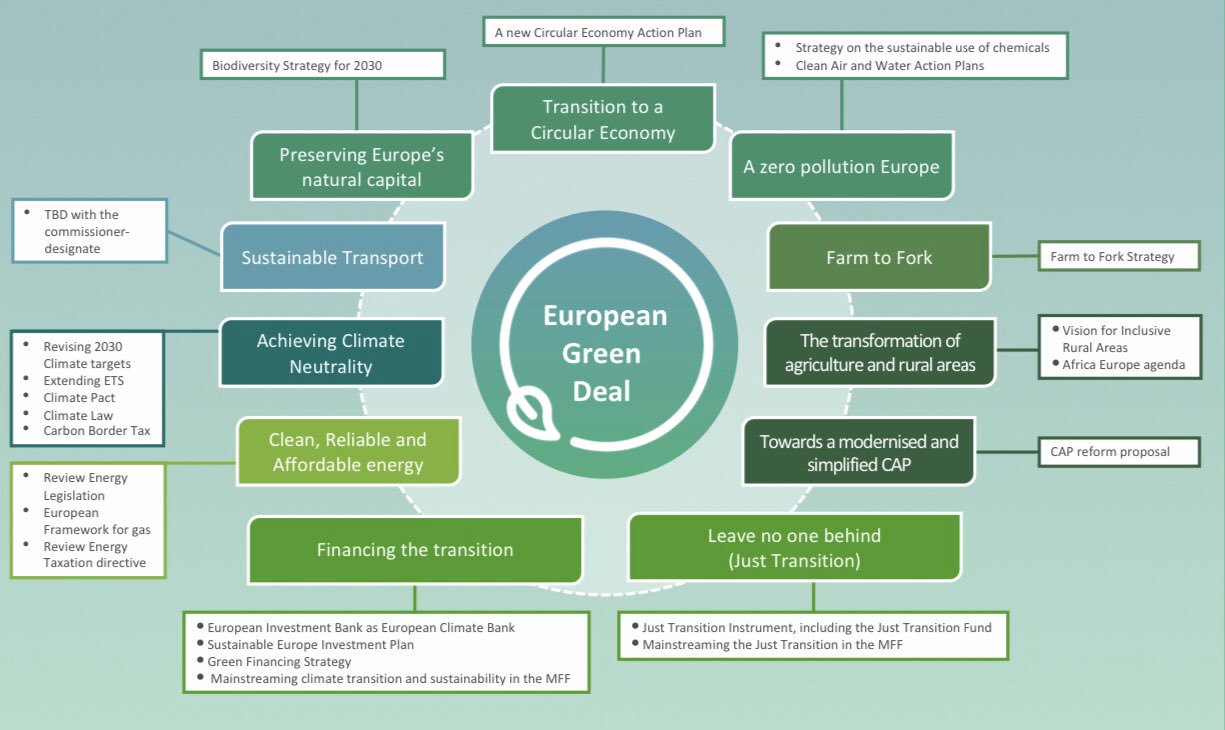

The European Green Deal is an action plan that aims to transform the European Union’s space into a fair and prosperous society, “with a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy”. But what makes it revolutionary is its comprehensive, pervasive approach, which is going to affect not only production processes, but also the economic system as a whole. It is a strategy for growth which is going to bring about changes in each sector of the economy.

As stated in one article published by the World Economic Forum, “the deal represents an unprecedented effort to review more than 50 European laws and redesign public policies”. The main areas of policy intervention are biodiversity, food systems, agriculture, energy, industry, building and renovating, and transportation. The deal’s ambitious objective is to create the “first climate-neutral continent” (EC, 2019) by 2050 through 3 mains goals: reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 40% by 2030, making economic growth independent from resource use, and making the transition as just and inclusive as possible, that is, “leaving no one behind”. Social fairness cannot be separated from a green revolution.

Image: European Council on Foreign Relations

What are the benefits the Green Deal will bring about?

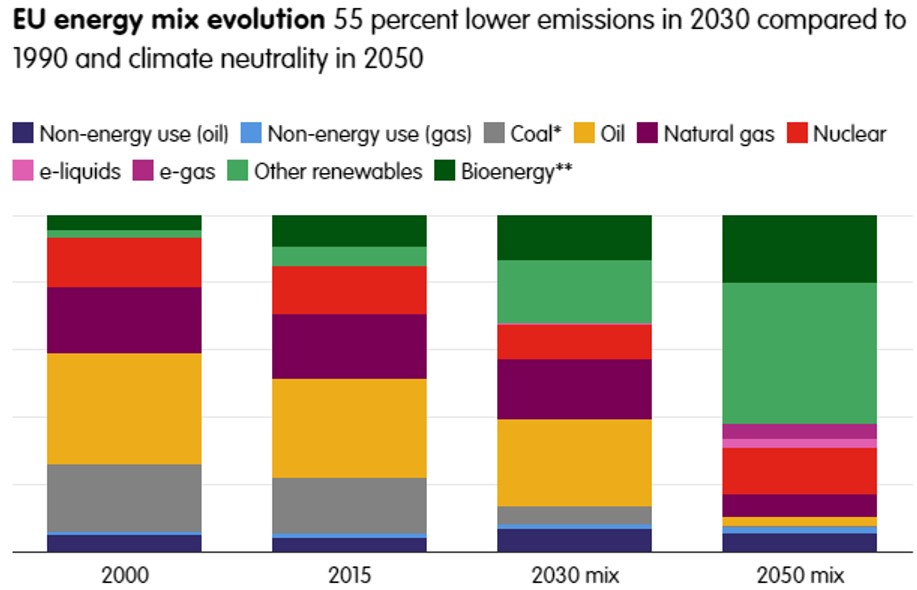

The first tangible benefits are the new laws and policies being proposed and approved in the past few years in order to reach the three ambitious goals set by the European Green Deal. The European Climate Law (July 2021), which sets the intermediate target of reducing net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, is one of the latest instruments created to make the targets legally binding for the countries. Another representation is the “Fit for 55” Package, a set of proposals aiming to align EU’s laws and policies with its overall climate targets. Carbon pricing, which is a mechanism to make polluters accountable on the basis of how much they pollute (‘polluter pays principle’), is another instrument that is being implemented to discourage firms from emitting without control and encourage them to update their technology. A further advantage has to do with awareness-raising. Citizens and communities are more aware of their environmental footprint. Households and firms will be more willing to switch to more energy efficient equipment and technology – such as smart buildings, energy-saving heating systems, electric cars – setting an example for future generations. Of course, countries still need to stop giving subsidies to polluting firms and being rigorous on carbon pricing and the EU needs to balance firms’ sustainability and competitivity.

One more aspect, which is also the most controversial, is the slow but steady transition to renewable energy. Most of renewable energy sources are clean (ex. nuclear energy, wind, sun…) and cheap, virtually free (ex. sun, wind, water…), most of them are very reliable and produce a big amount of electricity (ex. hydroelectric power stations and tidal generators). These sources are limitless as well, and this could solve the problem of EU’s dependency on other countries’ resources and prices, being subject to geopolitical choices and repercussions. Consequently, prices would be less volatile and economy more stable. The War in Ukraine and the closure of Nord Stream 2 are yet further proof that we need to become less dependent on fossil fuels.

What will the costs be?

As every revolutionary transition, the green transition will create both winners and losers, who will pay for the economic and social costs the transition requires. To finance this transition, the EU has already released 750 billion euros using the Next Generation EU Recovery Plan’s money. According to Business Beyond, ‘worldwide investments in oil and gas have decreased from 650 in 2014 to 300 million euros in 2021 and ‘with a rising energy demand, investments in renewables need to go up by four times’. This means that also the European Fund is likely not to be enough, so the risk of energy poverty is concrete. Important international players, such as China and India, will choose fossil fuels over energy poverty, making the EU’s effort to mitigate climate change useless since it is a global issue which cannot be localized.

Another preoccupation is the sustainability of the costs for small-size firms and low-income families, pressured to change equipment through carbon taxes, to which the costs of the new technology must be added. The already smaller and weaker actors will pay the highest costs, so that the EU will have to give up social fairness and face an increase in already-existing inequalities and asymmetries.

Unemployment will be another social cost: as many industries will phase out, many workers will lose their job. Some regions and countries (Eastern European member states), as well as some social classes (working class), will pay more. To counterbalance this ‘side effect’, more money will be needed to reskill workers and employ them in different industries. A great economic loss will also derive from old infrastructures, which will need to be reconverted. As for renewable energy, most renewable energy generators are expensive to set up. Also, sources such as wind and sun are not constant and are not powerful enough in some regions. This could cause great variability and instability in electricity production and availability.

Is green transition utopia or reality? And given its costs, is it worthwhile?

Many analysts and politicians believe in the efficacy of this plan and its policies in the long term, but this will require a joint effort. The green transition is possible, and it is already a reality but, of course, practice differs from theory, and theory remains a utopia for now. A part of these analysts, on the contrary, are more cautious about the success of this revolution because they think the cost to pay is too high, that the losers will be losing too much and, moreover, energy security, which is the main issue negatively related to climate change, cannot be guarantee by the renewables at the moment. If it is inevitable that some costs will arise with this transition – not differently from what has happened for every other transition that was ever put in place (just think about the Industrial Revolution) – it is fair to say that, actually, the benefits outnumber the costs.

With all its flaws, the European Green Deal is the best alternative we have to contain climate change and environmental damage. According to Carbon Tracker, an independent think tank researching about the impact of climate change on capital stocks and investment on fossil fuels, we have to act promptly to prevent this environmental process from becoming irreversible. This is an emergency and there is an urgency of acting. Our carbon budget, that is, the quantity of GHG emissions we are allowed to emit before reaching the established threshold of 2 Celsius degrees, is running out at a faster pace every year. If no major change takes place in our production processes and habits, 6 years and 315 days is the time we have left before it’s too late to take action and save our world for how we have known it so far. That is because, every year, we emit far more Co2 than the 300 tons limit. It is true that that this crisis has been exaggerated by mainstream media, which have increased alarmism but, even if we were given the benefit of the doubt about the time left, waiting more than we already have would not be wise.

The European Green Deal can guarantee intergenerational equity as well, based on intergenerational responsibility, a pillar concept of environmental law according to which we have certain duties towards future generations, and one of these is to preserve the environment we live in, and to mitigate the long-term adverse effects caused by our living habits. Instead of spending time and energy arguing about the downsides of the green transition which, by the way, nobody has the intention to deny, it would be better to focus on the best ways to implement the solutions currently available. On that respect, it can be said with a certain degree of certainty that the European Green Deal, with its practical policies and laws and forward-looking approach, is the best solution we can resort to right now.