Born to better achieve the Geneva Convention on the protection of refugees, the CEAS still does not overcome Member States’ priorities, forgetting perhaps guarantees.

The EU challenge: combine efficiency and greater responsibility sharing in a new pact for asylum policies.

When we hear talking about migration, there is always a lot of confusion and conflicting news. The European Union is struggling to manage the issue but let us understand why and how it works.

The EU level has shared competencies with the Member States in the area of freedom, security, and justice (Article 4(2)(j) Treaty of the Functioning European Union). In contrast, in the field of integration, the EU has a supporting role. While also clarifying the division of competences between the Union and its Member States, the 2009 Treaty of Lisbon (TFEU) expanded the Union’s functions. The Lisbon treaty has broadened the EU’s competencies concerning asylum, and even though this is still quite a still path, it tried to set out a legal basis for a Common European asylum system (CEAS). The EU can adopt measures to define entry conditions and residence conditions and standards that MSs should adopt for long-term visas and residence permits. Articles 79-80 of TFEU legislate on the migration of third-country nationals. Article 79 defines what must be understood as a standard policy on asylum, temporary protection, and subsidiary protection. Article 80 provides a legal basis for EU competencies on common immigration. What is meant by this expression is conditions of entries and rights for long-term and permanent statuses, family reunification, regulation to combat illegal immigration, and the competencies for combating trafficking. However, this article should not affect the right of MSs to decide the volumes of admissions: National governments remain responsible and detain the right to decide the number of immigrants they admit in their territory. The system of shared competencies that allows MSs to pursue their policies alongside the EU severely limited the EU’s consolidation and coordination roles, leading to fragmentation. Despite the European Union’s intention to raise a common standard procedure, the CEAS is not fully working and implemented today. Diverse acts, directives, and regulations are put together to form a pretty coherent system, but with several criticalities.

CEAS is fragile because it depends on the MSs’ interests, and they did not manage to arrive at harmonization of the Common Asylum Procedure.

The original part of such a coherent system was set up about 30 years ago when States decided to control and counter the free movement of Asylum seekers around Europe, looking for the best place to stay without being controlled and checked. The first Dublin Convention, signed as an international treaty among 12 EU countries, soon became a European Regulation, notably Dublin II, directly applicable within each Member State. Ten years later, Dublin III was adopted: ensuring that no asylum application remains unfinished, it focused on the following three criteria for determining which Member State is competent to scrutinize the application:

- the State where family members of the applicant are already present

- the State that issues the visa or residency permit

- the country where the request is submitted in the case of unaccompanied minors, who are considered a vulnerable category.

A fourth residual criterion, notably the State of first entry, remains the most applied.

At the moment, the first step to access asylum is to apply. The European State that receives the application decides on the status and grants it, and asylum seekers must stay in that country. Refugees do not necessarily have recognized their freedom of movement.

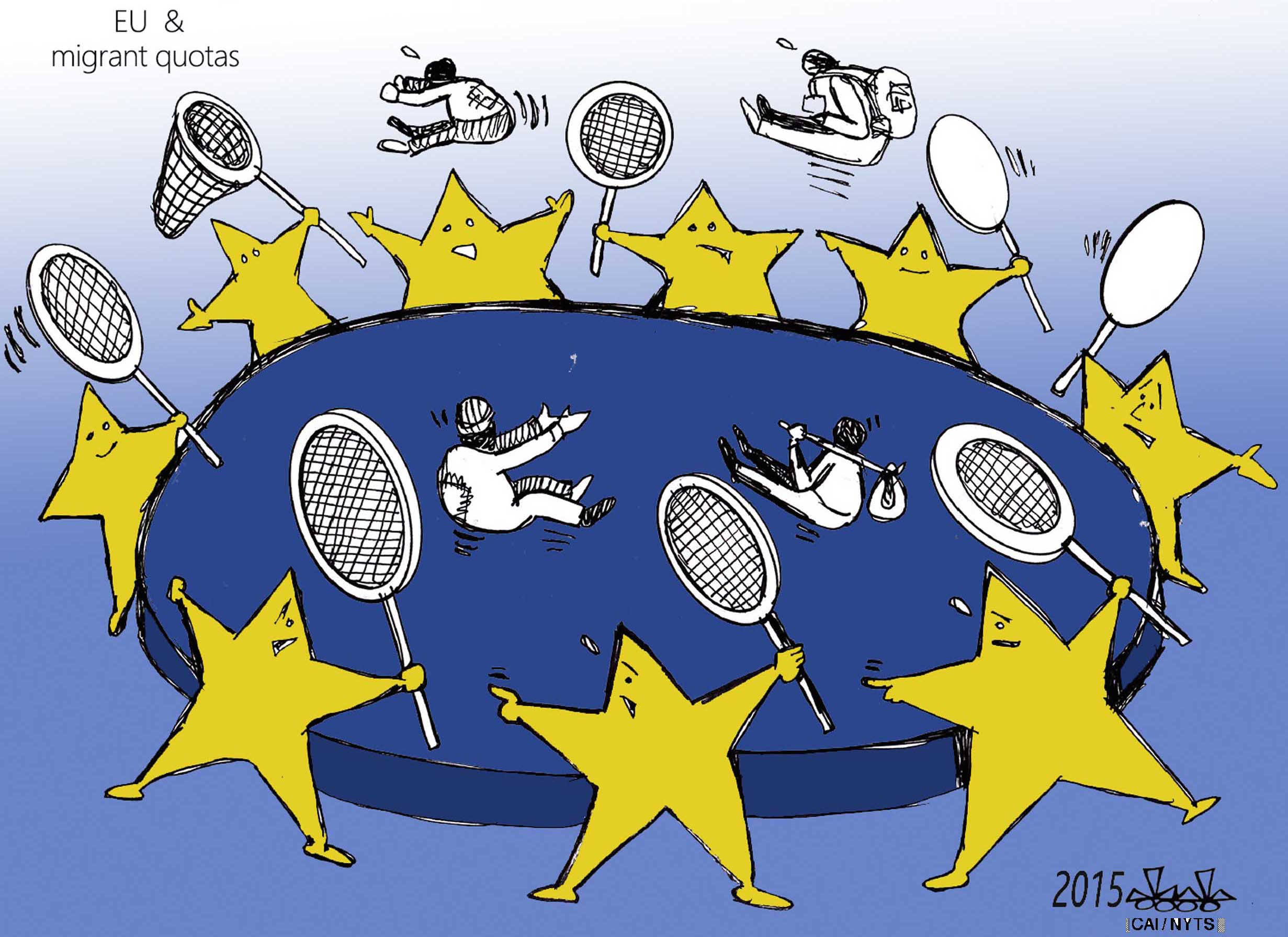

When it overcame the difficulty to identify which State is competent to scrutinize the procedure, other problems emerged. The first entry principle of the Dublin Regulation, which was thought to make the system fluid, avoiding multiple agreement requests among MS and the second movement, puts excessive pressure on frontline countries and forgets the responsibilities sharing concept.

Therefore, in addition to the burden which frontline states are loaded with, the issue of identification became crucial: migrants certainly do not look at the legislation concerning them in the country where they manage to arrive but when they do arrive, if it is not in favor of them, they will try their best to go to another country where the legislation is more convenient, avoiding being identified in the first one. For instance, during the refugee crisis in 2015, Greece and Italy were overwhelmed by people entering their territory but willing to go to north Europe. However, while the purpose of the hotspot system was to identify the highest number possible of refugees, those willing to cross Europe did manage without being identified.

Nevertheless, assuming that MSs are attaining to the legal framework designed above, the implementation of Dublin has led to the creation in every single Member State of an office to scrutinize the procedure, so if the application is lodged in Germany, it will go to the office responsible. A Dublin unity will do a preliminary job deciding if Germany is the right place for the asylum seeker; if not, they will send him back to the first country of arrival. It makes the process very long. It has often been argued that the system does not guarantee adequate protection for asylum seekers due to the highly lengthy nature of the assessment process. According to the European Asylum Support Office (EASO), during the first half of 2019, just some other 277,700 first-instance decisions were issued while some 439,000 cases were awaiting a decision at first instance in the EU, which represents an increase compared to 2018 (EASO, Latest asylum trends – June 2019, available here).

How is it possible? The fact that CEAS sets common minimum standards for the treatment of asylum seekers is not enough because the system of policies that evolved still left space for individual MS approaches. It means that each national asylum framework’s overall organization and functioning remain within the scope of governments. Now, where directives remain silent on structure features, differentiated implementation systems managed by Governments of MSs do not reduce the number of pending cases. Basically, organizing units based on countries of origin of third countries nationals or the grounds of special needs applicants could speed up the asylum procedure, improve efficiency and avoid spending resources inconsistently in the examination of applications.

MSs’ contribution to a uniform, fair and efficient CEAS by implementing their national asylum system is deeply affected by the number of resources spent.

So, according to the Asylum Procedures Directive (Article 2(f) Directive 2013/32/EU recast Asylum Procedures Directive), MSs are responsible for an appropriate examination to recognize those in need of protection correctly. It is included the obligation on MSs to provide authorities with appropriate means, knowledge, and necessary training in international protection. Moreover, asylum authorities must cooperate with applicants to assess all the relevant elements of the application, as giving, for instance, necessary guidance concerning the procedure to be followed (Article 4(1) Directive 2011/95/EU). The reality is that some determining authorities, apart from ensuring adequate living conditions in the reception facilities, also provide integration programs, such as advisory services for adults or language courses (Germany). Others may not. That is how the resource volume reflects the level of carefulness dedicated to the person’s conditions.

Over time, a progressive transfer in competencies to the European Community/ Union was probably meant to harmonize the Geneva convention objective better. However, in the end, adequate protection for asylum seekers depends significantly on a specialized and well-structured first-instance asylum authority, for instance. Otherwise, asylum seekers risk being confronted with lengthy procedures, less careful examinations, or even unfair denials of international protection.

A fair and effective asylum system does not depend only on the European Union. Apart from the unsuccessful sharing system of responsibilities (as a corollary of the Dublin System) and the lack of adequate protection and guarantees, not rarely have States relied on derogations or opt-outs rather than opt-in. Therefore, part of the failure to implement some of the agreed harmonized standards is also due to MSs self-interests.

The consequences, in the end, are that asylum seekers are not treated uniformly, and each MS can freely decide the number of people to allow in.

These constraints – put by the MSs’ resistances – limit the possibility of EU institutions to get involved and act firmly in the internal dimension of the migration and asylum system. Hence, the EU level attention has been transposed towards the external dimension of migration and asylum policies. Unpleasantly, this approach often resulted in short term decisions focusing on security threats inside the EU with the risk of being unsustainable or even incompatible with humanitarian standards, notably border management measures, such as the violent treatment against the migrants at borders in the Western Balkans.

Which attempts have been made to strengthen the CEAS fragilities?

The European institutions often tried to call for greater responsibility – sharing MS proposals of relocation and distributions policies, but no final deals were reached in every case. Based on all these previous outcomes, at the end of 2020, a new regulation on asylum and migration management was designated. The European Commission started consultation with the European Parliament, MSs, and various stakeholders on the New Pact on Migration and Asylum. In particular, the New Pact recognizes that no Member State should shoulder a disproportionate responsibility and that all MSs should contribute to solidarity constantly. It seems a sign of hope towards a new and more comprehensive idea of CEAS.

We are perfectly aware of how challenging could be to design policies compliant with humanitarian principles, supported by European voters, and call for a fair system based on shared responsibility. However, it is urgent as well the need to overcome these unbalances among the actors – and perhaps unconcerned approaches – which have characterized the European migrants and asylum system for too many years.