By Hamza El Moukadar, Mattia Morresi, and Chiara Vagli

The last ten years have been a very challenging period for the EU. The many crises that the Union has faced – starting from the Eurozone crisis – deeply affected people’s perception about the whole project and consequently the legitimacy of the Union in the eyes of its citizens. Indeed since the European elections of 2014, populist and Eurosceptic parties have gained significant results riding the wave of mismanagement, particularly of the sovereign debt crisis and immigration issue. The 2016 UK decision to leave the Union was probably the most symbolical event of that period of lost trust – the tip of the iceberg. However, the attitude toward the EU has not always been like that. From the late ’70s to now, the debate around the Union has constantly evolved, as it demonstrates, for instance, the use of the concept of democratic deficit – one of the building blocks of the EU critics nowadays.

The Democratic Deficit. How the concept has evolved

The debate around the democratic deficit of the European Union is a long-standing debate. It has been affecting the Union since the late ‘70s and has evolved together with it. Today the term is used to describe the lack of accountability and legitimacy of the EU institutions, though it was not the case in the past. However, the first time the term was used was by the Young European Federalists in their Manifesto of 1977, adopted in Berlin. At that time, the European Community was still in an embryonic stage of development. It was deemed, by the federalists, inadequate to face the current needs of a changing society. Their claim was for an even closer Union capable of addressing the city’s problems through the creation of “institutions capable of solving European-wide problems that have escaped the control of nation-states.” Their efforts were therefore headed to the direct election of the Members of the European Parliament. Today the democratic deficit has somehow changed its meaning, becoming the flagship of the Eurosceptic parties throughout the whole Union. The term implies not just the lack of democracy, as in the impossibility to challenge and reject the Commission, which is the government of the Union, but also addresses the complexity of the European system, which is increasingly perceived as a vast and complicated bureaucratic machine.

From a European Consensus to a European Dissensus

Another valuable perspective to better understand how the EU is perceived is shifting from the permissive consensus to the constraining dissensus. As Scheingold and Lindberg put it in the 1970s, “only if the Community were to broaden its scope or increase its institutional capacities markedly would there be a reason to suspect that the level of support or its relationship to the political process would be significantly altered”? That is what happened over the last 30 years, during which the Union enlarged its scope, borders, and functions, taking for granted that people’s mood about it was always the same while it was not anymore.

Nowadays, there is more and more evidence of this lack of trust toward the EU. We could think about the steady decrease of the turnout of the elections, the French and Dutch no’s to the Constitutional treaties, and the incredible results that many Eurosceptic parties have achieved during the last ten years, both at the European and national level. These are all examples and vital signs of how society has been changing its attitude toward the EU and how they should be taken into account to find a new path that will make the EU thrive again.

The specter of Populism in the EU

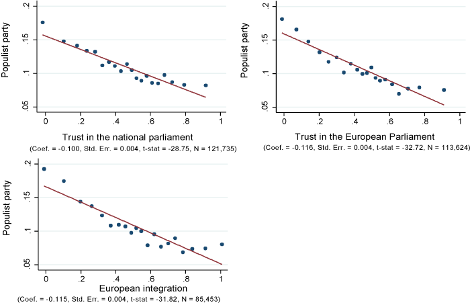

Starting from the lack of trust in the EU institutions and the democratic legitimacy issue, recent years have seen rising support for populist parties in most member States– especially since the early 2010s. The specter of populism itself has become stronger lately, in such an era of growing uncertainties that unfortunately led to a widespread mistrust in political institutions (also at the EU level). There seems to be a correlation between populist parties’ support (listening to the ones in need of constant reassurance) and little trust in the EU institutions and policies (especially after all the failures in the crisis management by the EU itself between 2008 and 2012).

An angry eruption of Populist insurgency (2014)

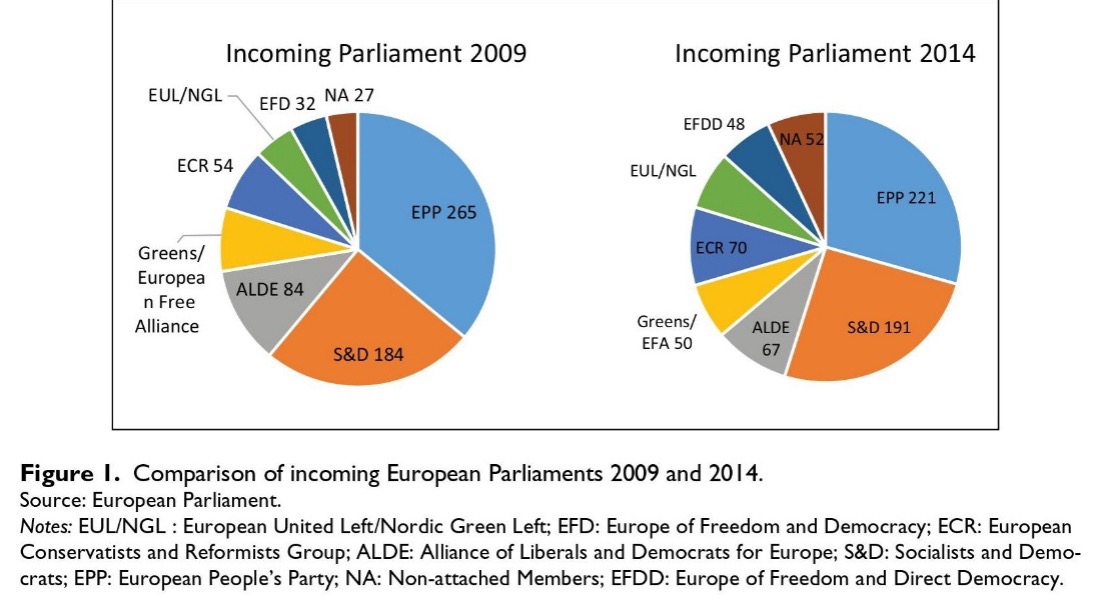

The years before the 2014 European Parliament elections were, therefore, a bit of a challenge for the EU as a whole; more precisely in terms of loss of confidence in the EU’s policies, democratic accountability (see, for instance, the dominance of the European Council in the decision-making process) and mistrust in the institutions. In other words, the 2014 European Parliament elections came while all of the social, economic, and institutional implications of the two major crises– the 2008 crisis and the Eurozone one- reached a peak. Therefore, it is no surprise that they resulted in “an angry eruption of populist insurgency, calling into question the very institutions and assumptions at the heart of Europe’ s post-World War II order.” More precisely, the rise of Eurosceptic parties, in terms of the composition of the European Parliament, is highlighted by the decline in representation of two of the three pro-EU groups (EPP, S&D, and ALDE) in less than five years.

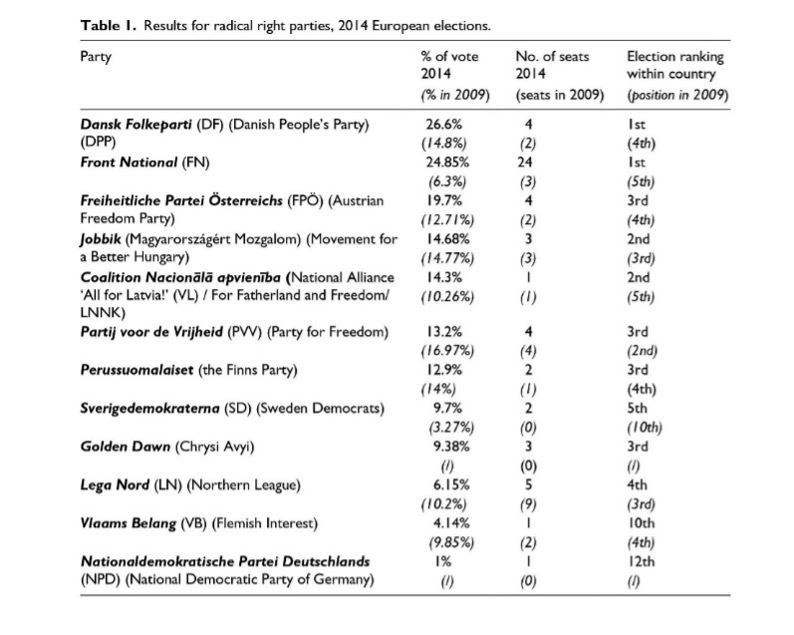

Whereas the most significant gains were made by radical right parties, especially in Western Europe (as shown in the table); instead, the situation was pretty different in Southern Europe since Eurosceptic radical left parties were much more prevalent due to their opposition austerity.

Euroscepticism and Populism: threats and remedies

Therefore, the rise of radical populist and eurosceptic parties highlights both an economic and a political crisis in European liberal democracy.

It dwells on the demands and aspirations by most EU citizens that felt like they were not taken into account anymore- especially since the two major crises started.

It is not surprising why the 2014 elections were a pivotal moment for anti-European forces.

However, given the unrest among many Europeans, “a long term intellectual and political project is necessary.” In other words, a reconstruction of the European political and economic model by reconciling all those values at the heart of the EU project itself (against any populist threat trying to bring them down with its Eurosceptic proposals) is more than welcome.

The origins of the Eurosceptic sentiment

Euroscepticism is nothing new actually; a few perplexities regarding the functioning of the EU first arose in the UK in the mid-1980s.

However, since the beginning of the New Millenium, the EU has faced more challenges. That eventually helped the Eurosceptic sentiment itself to grow among other member states- more precisely right after the Eurozone crisis that has affected the continent since 2008 and still has repercussions on member states themselves to this present day, both in the economic and in the political area.

One of the most striking examples of this is undoubtedly Brexit. By focusing on the latter, evidence shows that this same crisis, and how the EU institutions responded to that, was one of the leading causes that helped the Eurosceptic voice be heard. It was even screamed by populist parties, who claimed to be the people’s representatives against both the corrupt elites and the greed of the banks. This epochal event brought for the first time the awareness of this Eurosceptic sentiment that has culminated with the 2016 referendum.

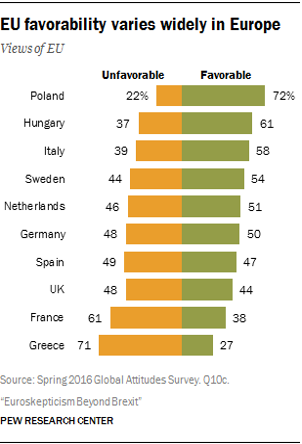

Moreover, while British people were called to the polls, the Pew Research Center stated that the Eurosceptic sentiment varied from country to country. As previously said, the EU has had several difficulties in handling some issues (e.g., the management of the recovery from the economic crisis and the issue of the more recent migratory crisis that has particularly affected the Mediterranean countries). In his work “A Touchstone of Dissent: Euroscepticism in contemporary Western European party Systems,” Paul Taggart, politics Professor at the University of Sussex, defines Euroscepticism as “the idea of a contingent or qualified opposition as well as incorporating outright and unqualified opposition to the process of European integration,” to remark that the origin of this same sentiment comes from the unwillingness of some member states do not contribute to the process of European integration, preferring instead to preserve national power as much as possible and to defend their borders as well.

Moreover, while British people were called to the polls, the Pew Research Center stated that the Eurosceptic sentiment varied from country to country. As previously said, the EU has had several difficulties in handling some issues (e.g., the management of the recovery from the economic crisis and the issue of the more recent migratory crisis that has particularly affected the Mediterranean countries). In his work “A Touchstone of Dissent: Euroscepticism in contemporary Western European party Systems,” Paul Taggart, politics Professor at the University of Sussex, defines Euroscepticism as “the idea of a contingent or qualified opposition as well as incorporating outright and unqualified opposition to the process of European integration,” to remark that the origin of this same sentiment comes from the unwillingness of some member states do not contribute to the process of European integration, preferring instead to preserve national power as much as possible and to defend their borders as well.

Is some Euroscepticism good for EU institutions?

In a democratic system, political opposition is an excellent indicator to enhance the degree of political participation. As Giles Pelayo, Head of Unit at the European Commission’s ‘Europe for Citizens’ program, said: “Scepticism is good, Citizens should be the controllers (of the European project). It is right that they are very demanding.” Euroscepticism, therefore, is used here as a tool to invoke direct democracy within the EU, emphasizing the concept of the democratic deficit of which the EU itself is accused and stimulating the growth of populist sovran parties.

The answer to the question can be pretty controversial. Euroscepticism might be suitable as it could boost EU institutions to focus more on its citizens’ civil status and improve their living conditions, rather than simply concentrating on institutional or technical aspects.

In other words, the EU should stem, as much as possible, the current populist wave by responding to the charge of democratic deficit and also by implementing policies that could improve the lifestyle of all EU citizens. Only in this way will it be possible to affirm that a bit of Euroscepticism could be helpful for the EU itself at the end of the day.