By Antonella Benedetto and Giulia Tessadri

By Antonella Benedetto and Giulia Tessadri

“China is a sleeping giant. Let her sleep, for when she wakes, she will move the world”. The prediction, inaccurately attributed to Napoleon and adopted one century later by Lenin, perfectly remarks on the reality of the Middle Kingdom as a new emerging power. Not surprisingly, the EU’s full agenda on China includes the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), (in Chinese中国-欧洲联盟全面投资协定) “the most ambitious outcome” – according to Marco Chirullo – “that China has ever agreed with a third country.”

The dynamics of EU-China relations

The cooperation between China and the European Union has been challenging over the years, mainly for two reasons: the different economic models and the imbalance in investment rules (Amal, 2021). The European Institutions, in March 2019, during the Communication “EU-China: A strategic outlook,” defined the simultaneous multilateral Chinese faces as “strategic rival,” “economic competitor,” or “cooperation partner” depending on the issue or policy area involved (European Parliament, 2020). This attitude was visible during the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) negotiation process. Finally, the last 30 December, the European Union, and China, after seven years of negotiations, concluded the Agreement, which reunited and implemented all the twenty-six bilateral agreements known as the Bilateral Investment Treaties (BIT).

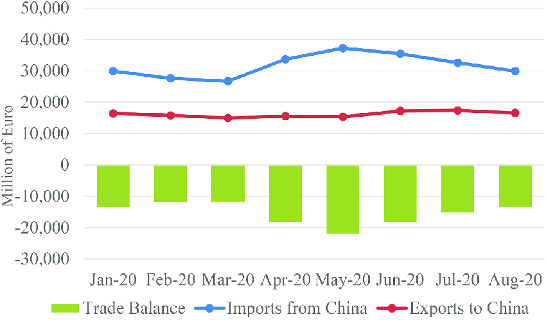

Why is this Agreement so important? China and the Old Continent celebrate 46 years of diplomatic relations this year. The two are the biggest trading partners globally; in particular, the European Union is China’s first trading partner, reaching up until August 2020, 382.3 billion euros in trading goods (Wang, Li, 2021).

After having joined the WTO in 2001, China liberalized a massive part of its economy. However, new rules needed to be fulfilled due to the progressive growth of trades and investments between the two counterparts and current global challenges: twelve years later, CAI negotiations were launched. The Agreement is based on three pillars: the implementation of transparency rules for Chinese state aid, equal conditions for all foreign investors, and shared rules on climate, health, and work protection: “The Parties reaffirm the right to regulate within their territories to achieve legitimate policy objectives, such as protecting public health, social services, public education, safety, the environment, including the fight against climate change” […] (Article 1, EU-China investment negotiations).

Many scholars agree that the strongest reason behind the negotiations’ conclusion is the European institutions’ awareness that the Chinese economy will be the one that will grow mainly in the next years. In addition, the Agreement will also facilitate the recovery from the pandemic due to the reduction of market and investment barriers, the increase of confidence of global investors, and the solidity of the international supply chain (Wang, Li, 2021).

Beijing has already adopted the Commission DG Trade-specific tool (2018/05) Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA), useful to identify the impact of low environmental standards on labor conditions. Most importantly, it has promised to ratify the International Labour Organization Conventions (ILO), which cover the respect of its fundamental principles and the protection of labor rights. However, no firm date was set for the signature (Fallon, Amal, 2021). Nevertheless, new divergences risk compromising the Agreement’s ratification and worsening the relationship between the two counterparts.

Human Rights’ elephant

Only a few months after December 2020 (China – EU Agreement conclusion) arose a bilateral crisis. The reasons derive from the vast divergences between the two colossi regarding perceiving human rights, social guarantees, and national security based on the national system’s values and principles.

It would be better to speak of incompatibility than system rivalry, which risks stuck the Agreement ratification. Beijing’s crackdown against Muslim Uyghur in the Xinjiang region has arisen a diplomatic crisis: Europe could not remain blind so that it imposed seeming low-key sanctions against Chinese officials. As a counterattack, China has pounced on the EU’s five members of the European Parliament with retaliatory sanctions. In March, Josep Borrell, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, said China’s sanctions on EU officials had created “a new atmosphere” and “a new situation.” “I am sure that when we present this report to the European Union Council, the leaders will discuss it and will take into consideration the last events,” said Borrell. Besides, China’s military approach against Taiwan and the repression of some democratic activities in Hong Kong put evidence a tough situation to tackle.

Lack of reciprocity

Other discouraging factors are the change of gear about the ratification of the ILO Conventions, recently put as a non-arguable topic, and China’s aversion for disclosing its boundaries and sharing its technology privileges. In fact, in 2018, China was listed as the 6th closest country in terms of business opening to foreign direct investment (FDI) on the OECD FDI restrictedness index. Moreover, as a heritage of state economy, the Middle Kingdom, seen as an enviable competitor for the technological edge, does not share the same principles and values in terms of digital governance. The European Commission, from its side, is in charge of individuating human rights violations and security risks tasks, particularly regarding cyber technologies related to surveillance and other emerging ones.

Bilateral relations and political abuse

Furthermore, it is essential to evaluate the Chinese way of exploiting economic and trade relations through a political lens. Sweden – China, and Sweden hold a bilateral agreement that risked failing in 2015 due to the detention of a Swedish citizen in China accused of alleged illegal activities in Hong Kong. Sweden’s communications regulatory body has also prohibited Huawei and ZTE from building the domestic 5G network in October 2020. Furthermore, Sweden suggested to the European Commission to impose sanctions on Hong Kong policymakers after last year’s crackdown on pro-democracy protests and the implementation of the security law.

China’s response was both legal and political. First, after the CAI Agreement conclusion, the tech company Huawei denounced the Swedish government for banning it from the 5G network construction. Then the Chinese government has also warned European countries from banning Chinese companies in the construction of the 5G network, threatening retaliatory economic sanctions.

Conclusions: an uncertain future

The CAI could succeed in trade implementation, liberalization, and completion of the economic process long forty-five years between the two Parties. However, currently, the ratification appears far-off time: the European Union’s fundamental values prevail over a more pragmatic Chinese trade policy agenda. At last, it always seems further the possibility for China to comply with the “European way of thinking” in terms of transparency and way of conceiving social issues.