By Francesco Bortoletto and Giulia Maini

As people living in the European Union, it is complicated for us to fully understand the life of a Palestinian both in Israel and in the occupied Palestinian territories (OPT). Thus, we encouraged our guest (Mohammad Arekat) to describe the difficulties of being a Palestinian in this context. This is the second part of our conversation with him.

«Being a Palestinian means living under an apartheid regime»

On his part, Mohammad has no doubt: he bluntly refers to Palestinians as living under an «apartheid regime». To be fair, this is something more than just our guest’s personal opinion. In fact, a growing number of high-level organisations and entities, both within and outside Israel, are increasingly resorting to the term «apartheid» (as well as «persecution») when addressing Israeli practices towards the Palestinians’ ethnic group (especially in the OPT).1

Among others, Israeli rights organisations Yesh Din (2020) and B’Tselem (2021), as well as Washington-based Human Rights Watch (2021), all point to substantial evidence that allows for considering Israel as responsible of apartheid policies.

According to B’Tselem, Israel acts following one principle: «advancing and perpetuating the supremacy of one group – Jews – over another – Palestinians». Crucially, the Israeli NGO makes the argument that the territory between the Jordan river and the Mediterranean Sea can no longer be considered as operated by two distinct regimes separated by the 1967 Green Line. Rather, the reality on the ground is that 54 years of «temporary occupation» and creeping annexations have effectively cemented the existence of a single regime, that of Israel, which is committed to establishing and maintaining Jewish supremacy over the whole area. Such a regime, the report concludes, can only be called by its name: apartheid.

This is achieved «by engineering space geographically, demographically and politically»: indeed, Israel has divided both land and Palestinians in the OPT into separate «enclaves». As a consequence, Palestinians enjoy different rights depending on whether they live in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, in East Jerusalem, within Israeli sovereign territory or scattered around the globe in the Palestinian diaspora (those in the latter category are permanently barred from entering both Israel and the OPT). The only common trait is that their rights are never equal to those of Jewish Israelis.

Also according to Human Rights Watch, a «threshold» has ultimately been crossed – although the Washington-based NGO does not go as far as labelling Israel as an apartheid state. It does, however, charge the Israeli government with responsibility for committing both apartheid-like practices and persecution. Moreover, HRW report asserts that the international community’s failure to hold Israel to account for these grave violations has allowed apartheid «to metastasize and consolidate».2

On its part, Yesh Din contends that the shift in language used by the Israeli government – from «disputed territory» with reference to the occupied West Bank to a policy of overt, though gradual, annexation – underlines «an admission of intent to maintain control». Israeli occupation is described as a «gargantuan colonization project» that finds its key component in the steady expansion of Jewish settlements. Denial of rights, resources and development to Palestinians and encouraged development for Israelis, coupled with «physical and legal separation» between the two: these are some of the central features of what Yesh Din describes as a fully-fledged «apartheid regime».

All the mentioned reports duly note that the 2018 Nation State Basic Law (that we already examined here) effectively made explicit what had previously been only assumed: namely, that Jewish Israelis are methodologically privileged and that other groups, and specifically Palestinians, are institutionally discriminated against.

In the words of our guest, «only Jews are entitled to have rights», whereas «all other ethnic groups are considered as second-class citizens». Mohammad assumed that according to this document «we, as Palestinians, are discriminated in a legal way. We justhave to accept it». He also added that, as things stand in Israel, «I would have more right as a refugee in Italy».

Now, making use of the term apartheid is one serious accusation. Indeed, the crimes of apartheid and persecution are defined as crimes against humanity under international law, as they constitute extremely hideous violations of the most basic human rights.3

More specifically, the crime against humanity of apartheid is defined in both the 1973 International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid and the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) – in which the crime of persecution is also defined.

Considering the two sources jointly, for specific acts to amount to apartheid three criteria must be met: the contemporary presence of (a) an intent to maintain a system of domination by one racial group over another; (b) a systematic oppression of the latter by the former; and (c) inhumane acts perpetrated on a widespread or systematic basis.

In the same fashion, the crime of persecution is defined as (a) severe abuses of fundamental rights committed on a widespread or systematic basis with (b) a discriminatory intent. The prohibition of apartheid has become jus cogens, meaning that it accepts no suspension or derogation whatsoever.

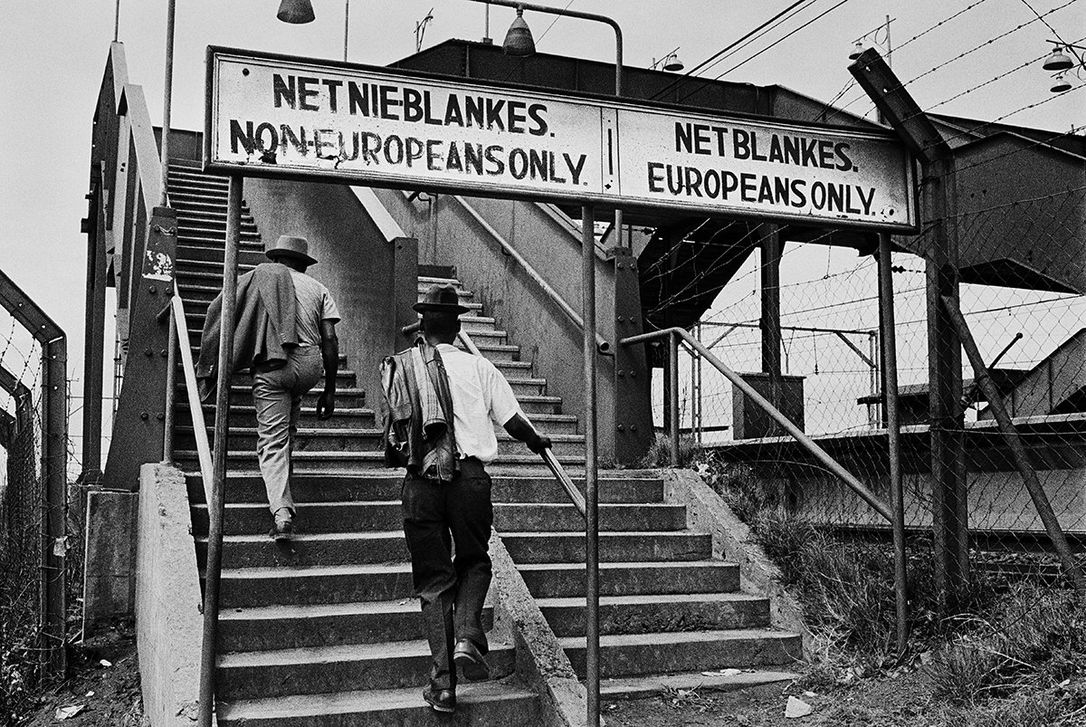

The term apartheid was originally used with specific reference to the regime of institutionalised segregation that took shape in South Africa and Namibia in the second half of the 20th century (it means «separateness» in Afrikaans). There, segregation had been formalised through as many as around 150 laws that officially disenfranchised the black majority in order to secure permanent domination by the white minority.

In the following decades, the term has been progressively detached from that particular context and came to designate an independent category of criminal («inhuman») acts perpetrated in pursuit of domination of one racial group over others. For the purpose of defining «racial discrimination», the «racial» element can also be grounded on ethnicity (and not narrowly on skin colour), according to the 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD).

This is why it has been increasingly resorted to with reference to the situation in the OPT, notwithstanding the lack of a specific body of law providing for formal discrimination of Palestinians. Indeed, commission of the crime of apartheid is connected to the actual practices carried out by a regime, rather than to the official acts or statements by that very regime or its representatives.

However, the situation in Palestine is anxiously monitored by the very protagonists of the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. Ronnie Kasrils, a former government minister, said he was worried that critical voices levelled against «apartheid-like» Israeli policies were being dismissed as anti-semitism, in that it is the same form of de-legitimation that the apartheid government of South Africa used against its own critics. For Desmond Tutu, winner of the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize for standing against apartheid in South Africa, the «humiliation» faced by Palestinians is reminiscent of apartheid in his country.

Mohammad told us that «there is a lack of healthcare assistance for Palestinians». Under international law, Israel is responsible for the welfare of the population it controls as an occupying power (as also discussed in the previous episode of our interview). This obligation crucially includes access to health services.

As a matter of fact, Israel is a member of the World Health Organisation (WHO), thereby recognising the universal right of the individual to health. Moreover, the country also ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, whose provisions are legally binding on its signatories.

However, according to a 2013 WHO report, access to healthcare facilities in the occupied West Bank and the Gaza Strip are subject to delays incurred by the need to seek permits from Israeli authorities. «Permits are difficult to obtain», since «there are no published eligibility criteria» to obtain them. One key motivation for Israeli authorities to refrain from conceding said permits, however, are «unexplained security reasons». Restriction of access to healthcare, the report recalls, is a violation of basic human rights under international law.

The WHO maintains that ambulance transfers are also far from easy. Indeed, they experience frequent, unmotivated, and time-consuming delays, «even when the referring hospital and receiving hospital have obtained prior coordination from the Israeli Civil Administration to transfer a patient through a checkpoint». In another report it was observed that more than 70% of permission requests in the Strip were denied in 2016, while in 2017 more than 43% got delayed.

Our guest said that, due to delays and controls at checkpoints, «a lot of children were born there because their mother had not arrived at the hospital on time». However, he said that this does not happen only with births, but also with deaths, «a lot of people died at checkpoints because they did not make it to the hospital», our guest told us.

Mohammad also talked about Covid-19 and the vaccination campaign. He told us that, even though the occupying power should take care of the health of people under its control, «the Israeli government only vaccinated Jewish people».

As reported by Médecins Sans Frontières, «you are over 60 times more likely» to get vaccinated in Israel than in the OPT. Incidentally, while Israel has arguably rolled out the most efficient vaccination campaign in the world, Palestine must rely on the COVAX programme (international aid to poorer countries).

According to estimates, Palestinians who got at least one dose were around 7,3% as of June 5. However, the only Covid-testing laboratory in the Gaza Strip got blown up by the IDF airstrikes in the last military escalation (Operation Guardian of the Walls, May 10-21).

The European Commission notes that 2.5 million Palestinians (out of 5.2 million) were in need of humanitarian assistance as of late May. In the occupied Gaza Strip, where around 80% of the population is dependent on foreign aid, the local economy has been «crippled» by the combined effects of the decade-long blockade, 3 wars in the last 12 years, as well as political divisions.

Gazans are trapped in a cycle of poverty, unemployment and food insecurity. They have limited access to basic services such as clean water, electricity and medical care, and few educational or economic opportunities. In the occupied West Bank, about 900,000 Palestinians suffer similar restrictions to their most basic human rights.

In the wake of last May violence escalation, over 250 Palestinians died in the Strip, including several dozens of children. About 100,000 fled their homes across the Strip.

Notes

- Reference to this term in the context of Israeli practice vis-à-vis Palestinians in the OPT is by no means new. The first voices denouncing violations potentially amounting to apartheid had already emerged in the wake of the Second Intifada (early 2000s), also owing to the construction of the so-called «Separation Wall» in the occupied West Bank. At first, most such voices were Palestinian; then, through the years, the term has been used ever more widely.

- It should be noted, however, that ascertaining the commission of the crime of apartheid does not automatically imply labelling the regime under which the crime has been committed as a fully-fledged «apartheid regime». This nuance is at the basis of slightly differing interpretations and assessments by different reports.

- The notion of crimes against humanity has evolved both under customary international law and through the jurisdiction of international (criminal) courts. As reported by the UN, this specific type of crimes has not yet been codified in a dedicated treaty of international law; nevertheless, its key components are set out in the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC Statute defines the crimes against humanity as composed of a physical, a contextual and a psychological/mental element: a specific inhuman act must be committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population, with knowledge of such attack (intentionality).